CANOPY SCIENCE...

...and the Life Epiphytic.

REVIEWER

Colin Forest

Search Analyst

Colin is a Search Analyst working for an international culturalisation and localisation organisation. With a focus on facilitating communication and understanding cultural nuance in Search, Colin’s role has been geared towards encouraging companies, communities and individuals to more effectively receive and disseminate information.

AUTHOR

Robin Hayward

PhD Researcher

Robin studies the way that tree seedling communities recover after logging in the Malaysian rain forest. They have worked previously to survey the structural habitat of both Asian and Caribbean island forests, coordinating citizen science groups, as well as completing the first canopy survey of epiphytes in Pulau Buton, Indonesia.

Canopy Science and the Life Epiphytic

Tropical rain forests have been a source of boundless fascination and discovery for as long as people have been exploring them. From Victorian naturalists like Wallace and Darwin who found their inspiration for theories of natural selection, to the latest advances in medicines and climate change mitigation, rain forests have revealed countless key insights to the workings of our natural world. Despite this however, there remain vast ecosystems that we have yet to study in depth and the largest of these is surely the canopy, which comprises pretty much everything at the tops of the trees.

Aside from the deep ocean, the rainforest canopy is probably the least studied natural ecosystem on the planet and the reason why is obvious — trees can be over one hundred metres tall! Because of this, getting to the top of them is understandably tricky and it wasn’t until fairly recently that the worlds of climbing and academia came together and the field of canopy research truly took off. Before that, most studies of canopy species relied on either smoking them out of the tree or shooting them down with a rifle.

People have been climbing trees in the tropics for many years. The progress of western science towards an exploration of the canopy has largely taken a separate approach from local methods however, with Sir Francis Drake supposedly becoming the first European to see the Pacific Ocean, having summited a large tropical tree in 1573 (Lace, 2009). The story tells us that he marched halfway across the Isthmus of Panama to this tree following a tip off from an escaped slave.

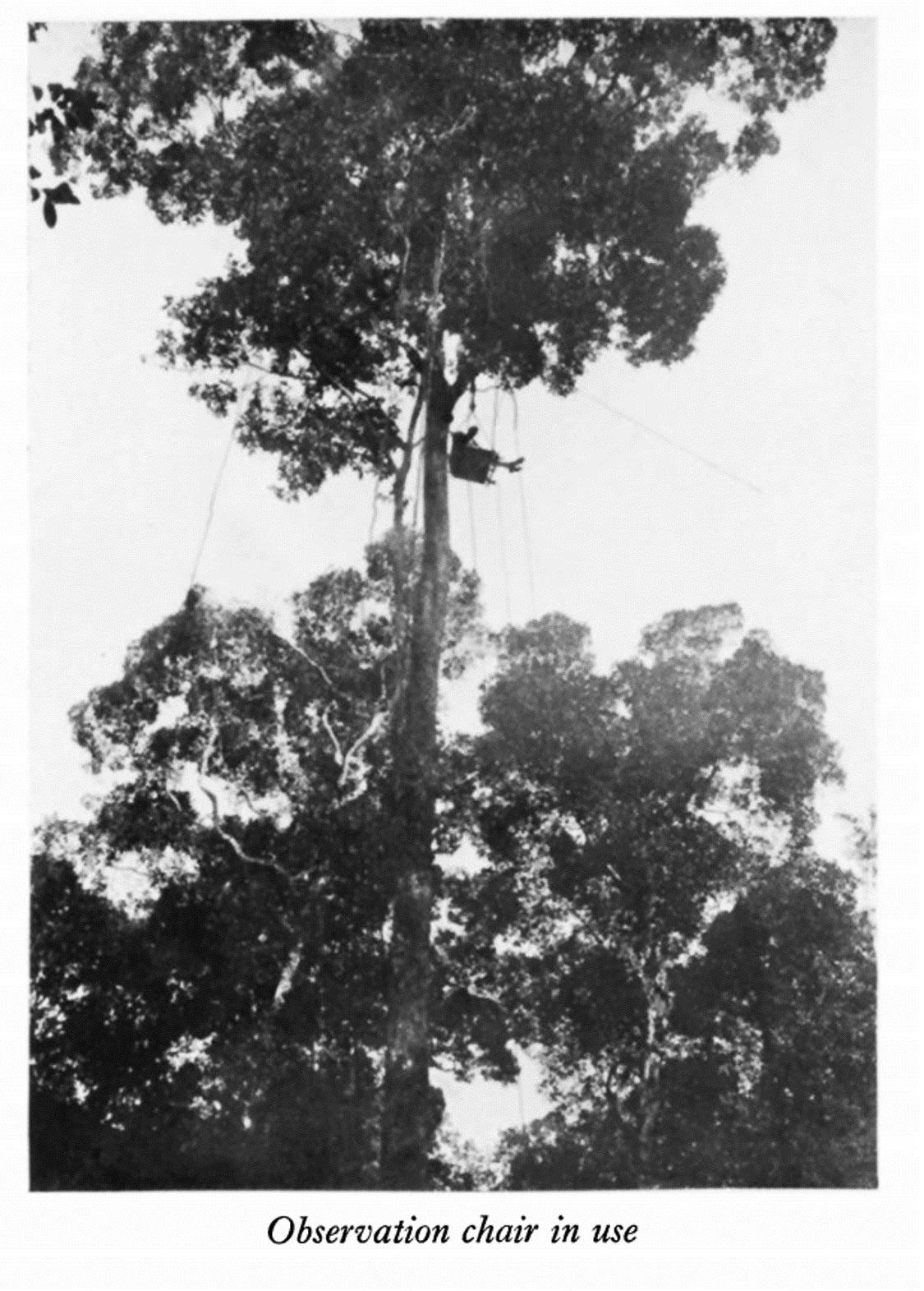

Three hundred and fifty years after that, in 1929, a team of scientists from Oxford University began the first scientific climb to study the rainforest canopy in Guyana. The tree had to be climbed first by locals with spiked boots in order for them to attach ropes to the tops which would allow the scientists’ ascent to be made from the comfort of a suspended armchair (Hingston, 1930). The results of this research were enlightening and showed great promise for the beginning of a new scientific field. It was not until the sixties however, that more studies of the canopy started to emerge in the scientific literature. Two notable journeys include a Dutch expedition to Zaire which involved the construction of platforms from which monkey behaviour was observed, and an American who built an eight storey high ladder in Malaysia to reach his own research goals in the canopy…

Fast-forward another sixty years and you might wonder what’s changed when it comes to my own canopy expeditions. For a start, I am sadly bereft of comfortable armchairs from which to observe the goings on of the rainforest and I certainly try to avoid using ladders too. Instead, everything is streamlined to be light-weight, portable, and as safe as is reasonably possible. This all means I can climb faster, with fewer assistants, and cover more ground each day. The result is a drastic increase in spatial data, allowing me to build a far more comprehensive view of the canopy ecosystem than past groups who have used complex contraptions with more limited mobility. While I take the minimalist route to the canopy, other researchers still build platforms and high-tech cranes which allow them to more comprehensively monitor a much smaller area. In the end, it’s all really cool stuff and we need every bit of data we can gather!

In this treetop world of staggering complexity and so many unanswered questions, it can sometimes be difficult to narrow one’s focus to a single point of interest. For me however, I can think of nothing quite so fascinating as the epiphytes that live up there.

Epiphytes are plants that spend their whole lives in the canopy. They are completely isolated from the ground throughout their entire life cycles and are utterly vital to the continued functioning of rainforest ecosystems. Without their ability to store water in the treetops after rainfall, many animals would regularly have to put themselves at risk from predators by making the long and tiring climb down to the forest floor to drink. Some species of epiphyte are known to hold so much water that they can even host frogs in the canopy too, without the need for grounded pools. Their use to the ecosystem goes beyond just water though; they provide habitats for insects, who then subsequently defend their host trees as well as producing enough food to supply up to a third of all bird foraging in some regions of the tropics (Nadkarni & Matelson, 1989).

The value of epiphytes is seemingly endless and yet globally, we still know remarkably little about them the world over. The majority of what we do currently know about epiphytes comes from just a few sites in South and Central America, while other regions remain relatively understudied (Barker & Pinard, 2001). Often, all we really know about epiphytes is that they are important and threatened by forest disturbance through human activities. How though, are we supposed to prioritise their conservation when we can’t know exactly where they are most diverse without long and expensive climbing campaigns to observe them? The answer is: by observing the trees on which they grow and improving our understanding of the epiphyte-host relationship so that we can predict their distributions.

For almost two months, I carried hundreds of metres of rope into the forest with Ben and Asinu, my friends and colleagues who each had specialist expertise in climbing and forest survival. Together we used catapults to launch our climbing gear into the trees and provide us access to the canopy, fifty metres above our heads. Slowly, making sure to watch out for the spiked vines and angry insects whom we were likely to disturb with our presence, we would haul ourselves skywards.

Inch-by-inch as you ascend the rope to the canopy, the rainforest vista becomes more and more impressive. Eventually, and if the tree is tall enough, you can see as a bird might, right the way to the island’s coast in one direction and across to rolling hills of forest in the other. Beneath, you can feel the living sway of the tree as it bends with the wind and in that moment it is hard to not be awed by this hidden world so high above our usual focus as humans.

After some time of simply enjoying the canopy, it always came time to take notes and complete our research. We tried our best to identify each epiphyte we could see (sorting by shape and characters when we couldn’t determine their names) and we measured their height, size, and location on the branch. Back on the ground, we measured the tree itself. Everything that was available to us, we tried to record. From the texture of the bark, to the diameter of the trunk and the area shadowed by its branches, we thoroughly classified each tree.

After a great deal more work, this time under the glare of computer screens instead of the Indonesian sun, all this climbing resulted in the publication of my first academic paper in the Journal of Tropical Ecology (Hayward, 2017). We found through models of our different measurements that tree size was by far the greatest indicator that a tree would be host to a high diversity of epiphytes. The other properties of individual trees were largely meaningless, with even the texture of the bark (something we had assumed would be important for determining how easily an epiphyte could grip the branch) having no significant effect.

This is just one conclusion amongst the growing body of research on epiphytes and canopy ecology in a field of study that continues to reveal exciting and unexpected ecologies. New climbing techniques continue to be innovated and now drones, mounted with high quality cameras, are on the verge of revolutionising data collection in the field. With more information available to us than ever before, I am confident that in time, the canopy will be recognised to be just as valuable a conservation focus as the systems of the forest floor. I look forward to uncovering more of its secrets!

REFERENCES

Barker M.G., Pinard M.A. (2001) Forest canopy research: sampling problems, and some solutions. In: Linsenmair K.E., Davis A.J., Fiala B., Speight M.R. (eds) Tropical Forest Canopies: Ecology and Management. Forestry Sciences, vol 69. Springer, Dordrecht

Hayward, R., Martin, T., Utteridge, T., Mustari, A., & Marshall, A. (2017). Are neotropical predictors of forest epiphyte–host relationships consistent in Indonesia? Journal of Tropical Ecology, 33(2), 178-182. doi:10.1017/S0266467416000626

Hingston, R. (1930). The Oxford University Expedition to British Guiana. The Geographical Journal, 76(1), 1-20. doi:10.2307/1784676

Nadkarni, N., & Matelson, T. (1989). Bird Use of Epiphyte Resources in Neotropical Trees. The Condor, 91(4), 891-907. doi:10.2307/1368074

Lace, W.W., 2009. Great Explorers: Sir Francis Drake.